SPAIN

BOTANICAL GARDEN OF MADRID

Discovering a New World

Photographs of Cristina Archinto

Text Carla De Agostini and Alessandra Valentinelli

In the centre of Madrid, there is a secluded place where it is still possible to enjoy nature and calm, in the shade of large trees and away from the urban chaos: the Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid in Plaza de Murillo, a stone's throw from the Prado Museum. Full of evocative corners covering more than two centuries of history, the Botanical Garden is a living encyclopaedia open to anyone who wants to discover its plant treasures, with a collection of more than 6,000 species, most of which are of Mediterranean origin (southern Europe and North Africa) and from other areas with a similar climate, such as California, Argentina, Chile, South Africa and southern Australia. The Garden has always been a reference point for botanical research and knowledge, and under the aegis of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, the Spanish Higher Council for Scientific Research, it was declared a National Monument in 1947.

The Garden was opened in 1755 and initially placed on the banks of the Manzanares River by order of Fernando VI, a botany enthusiast. Then, in 1781, Carlos III moved it to the Paseo del Prado where, designed by the architects Francisco Sabatin and Juan de Villanueva, to whom we also owe the Prado Museum and the Astronomical Observatory, the Real Jardín was arranged in different terraces inspired by the Paduan quarters: On the orthogonal plan of the Orchard, Sabatin and Villanueva placed circular fountains at the corners, then built a greenhouse pavilion, now the Villanueva Pavilion, the Herbarium, the Library and the Botanical Hall, as well as the Royal Gate, once the main entrance, in the classical style with Doric columns and pediment.

Since its inception, the Real Jardín Botánico has been a privileged place for research and teaching. In fact, it has an immense cultural heritage, the fruit of scientific expeditions carried out during the 18th and 19th centuries, preserved in the Herbarium, Library and Archives. In 1755, Charles III of Bourbon decreed that the Real Jardín Botánico should be the place where all the materials from the scientific expeditions he promoted would converge. In ten years there were four such expeditions: to Chile and the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1777, to Colombia and New Granada in 1783, to New Spain in Mexico and Guatemala in 1787, and to the coasts and islands of the Pacific in 1789. The Garden became the final destination of a network of experts, technicians and researchers who brought drawings, herbaria, seeds and sometimes plants to Madrid. One of the last expeditions was that of Alessandro Malaspina, a captain in the Spanish navy, who sailed from Cadiz to Montevideo in 1789, touching Chile, Peru and Panama, and going as far as Vancouver, Manila and Macao. Returning to Spain in 1794, without the defence of the now deceased Charles III, he ended up imprisoned for his ideas of brotherhood between nations, and then exiled. In fact, Malaspina's philosophy transcends political and military conflicts, and he promotes an exchange of measuring and navigational instruments, books, observations and naturalistic knowledge, which is why he used to leave with a mixed crew, including Germans, French and Italians, accompanied by the best English and Bohemian instruments. Convinced that there is no 'land to discover but a world to know', the cartographers who map coastlines and islands with him then share them with the hydrographic offices in Paris and London. His naturalists, crossing the Andes, inventoried fossils and species with direct analyses that would later perfect the Linnean system.

To date, the plants on display are organised on four terraces that take advantage of the irregularities of the terrain. At the corners of the quarters, i.e. the smaller squares inscribed in the geometric design of the individual terraces, are tall, towering trees that serve to refresh and distribute the plant groups. The first terrace is the lowest and most spacious of all, the Terraza de los Cuadros, where the collection of ornamental rose bushes, ancient medicinal and aromatic plants stand out, impregnating the air with unexpected scents along with the fruit trees. Here, the first plants to bloom in January are hellebores, followed by daffodils and crocuses. In April and May one can admire lilies, peonies and roses, and in the warmer summer months the beautiful dahlias appear, colouring the whole garden. The Terraza de los Cuadros is a catwalk of blooms, among the most pleasant in terms of scent and view, where one is always accompanied by the chirping of colourful species that, depending on the season, find solace in their favourite foliage.

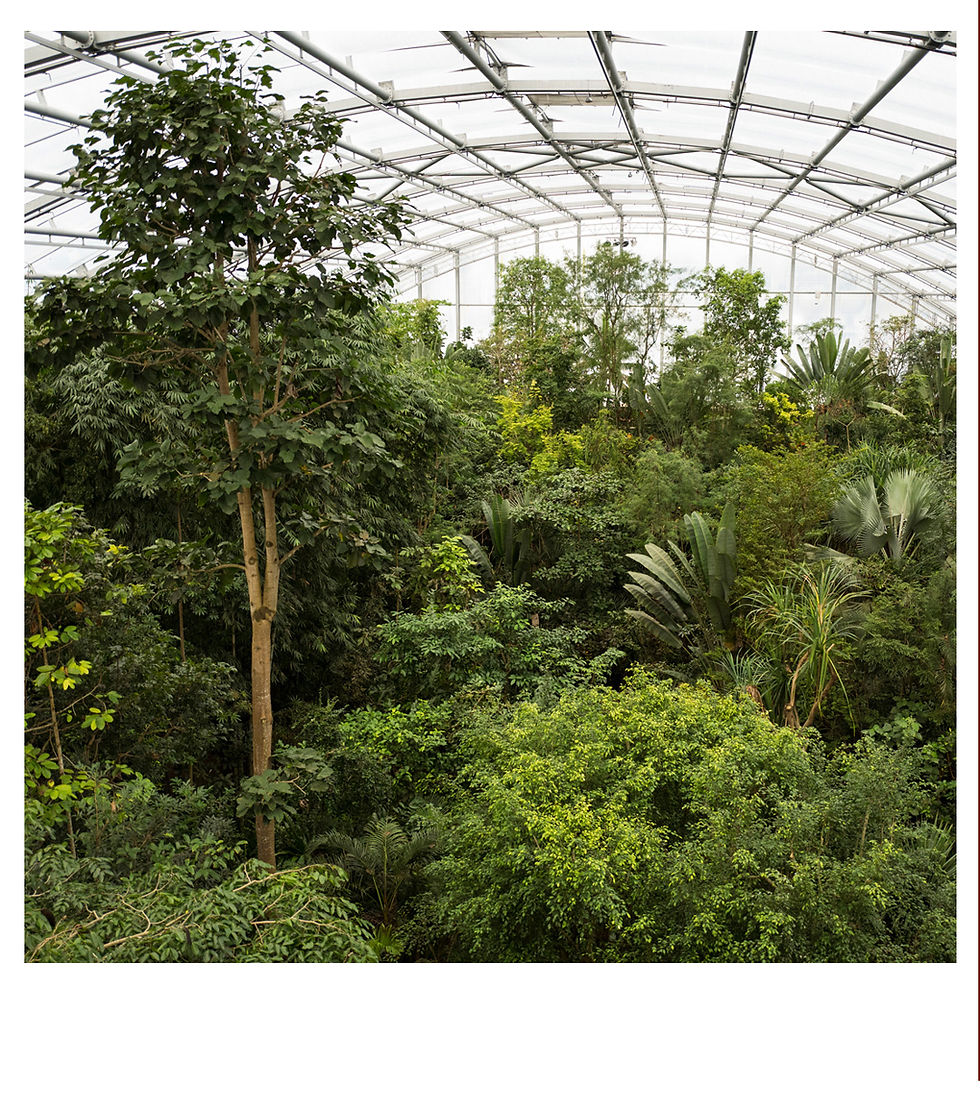

The second terrace, smaller than the previous one, houses the taxonomic collections of plants, which is why it is called Terraza de las Escuelas. The vegetation is arranged phylogenetically by families, so that the order of the plants can be traced from the most primitive to the most recent. Then there is the romantic-style Plano de la Flor, which houses a great variety of trees and shrubs planted in random order. The terrace is bordered by a wrought-iron pergola, made in 1786, with different varieties of vines, some of them of remarkable age. On the eastern side is the Villanueva Pavilion, built in 1781 as a greenhouse and currently used as a gallery for temporary exhibitions. It is an important centre for bringing the public closer to science and biodiversity through the creative and alternative languages of ever-changing artists. Many exhibitions seek inspiration in the Garden's own Archives and Herbaria, with the aim of creating a plant culture through the dissemination of a scientific didactic heritage as broad as that of the site. Finally, there is the Terraza de los Bonsáis, which houses a collection of bonsai trees donated in 1996 by former Prime Minister Felipe González, consisting of Asian and European species, mainly of Spanish flora, and expanded over time. On the north side is the Graells greenhouse, also known as Estufa de las Palmas, a wrought iron and glass greenhouse, built in 1856 under the direction of Mariano de la Paz Graells, the then director. This room mainly exhibits palm trees, tree ferns and banana specimens of the Musa genus.

FEATURED

PEONIES BETWEEN LEGEND AND REALITY

Peonies, or Paeonia, have always been prized for their beautiful flowers that fill borders in shades of white, pink and red from late spring to mid-summer. Since antiquity, the Peony has been known for its miraculous virtues: its name derives from the Greek paionía, meaning 'healing plant', in reference to its roots with important healing, calming, antispasmodic, sedative and even pain-relieving properties, an etymology it shares not coincidentally with Paeon, Peon, the Greek God of Medicine. A well-known Greek legend has it that it was Zeus who transformed Paeon into a beautiful, immortal flower, to save him from the wrath and envy of the master who had seen himself outwitted in the treatment of Hades. The peony has been competing for millennia with the rose for the title of most beautiful in the kingdom, and in China it is officially the winner with the appellation 'Queen of Flowers'. The story goes that more than 2000 years ago, Empress Wu Tutian, who was very beautiful but also very despotic, ordered all the flowers in her kingdom to bloom one winter morning. Fearing her wrath, the flowers agreed to comply: all except one, the peony. Furious at this proud refusal, the empress gave orders for every specimen to be uprooted and exiled to high, snow-covered mountains. The plant withstood the frost and bloomed magnificently in the spring. At that point, Wu Tutian recognised its strength and revoked its exile, giving it the royal title. The peony referred to in the ancient Chinese legend is the shrub peony, which is very rare in nature, and culturally for the Chinese, rarity coincides with preciousness. This is why a supernatural origin is attributed to it: in the Huashan Mountain Nature Reserve, 'Mountain of Flowers', from hua flower and shan mountain, in the Chinese region of Shaanxi, there are pavilions depicting the birth of the peony as the fruit of the union between a farmer and a goddess who gave him one as a pledge of love, before returning to the heavens. In antiquity, it was the exclusive privilege of the imperial family and the mandarin nobility to be able to cultivate it in their gardens, whereas today its aristocratic beauty is within everyone's reach. In European gardens it arrived in 1789, after a long voyage on an English ship only five plants managed to take root in Kew Garden for the first time that year.

Links

Moutan Botanical Center

GALLERY